Quantitative data from Egyptian businesspeople shows that the Egyptian military has a remarkable degree of importance as both customer and supplier for their businesses.

The Egyptian military, led by President Fatah al-Sisi continues its growing domination of the country’s political, economic and social institutions. While military-run governments are nothing new in Egypt nor the Middle East, one area that sets Egypt’s rulers apart is the close symbiosis between military officials and profit-seeking activities. In this blog post I describe research employing online surveys targeted at businesspeople and the Egyptian military from 2017 to 2020 that provide additional evidence about how these ties are affecting Egypt’s economy and politics. In brief, employing quantitative data from Egyptian businesspeople shows that the Egyptian military has a remarkable range of business activities across sectors that is an order of magnitude higher than other Middle Eastern countries.

The amount we know about the Egyptian military’s economic enterprises continues to increase, thanks to the enterprising work of journalists and researchers, combined with the military’s higher prominence in the country. While we knew that the military had an unusually high number of investments in a range of non-defense activities prior to the Arab Spring, recent publications by Zeinab Abul-Magd and Yezid Sayigh have opened the door to fully understanding the long-run historical trajectory of the military’s economic prowess. Since the Nasser regime (1956-1970), military personnel in Egypt have taken on managerial positions in state-owned enterprises which have often then led to private engagements following retirement (or even before leaving the service). At the same time, parastatal arms of the military, originally created to encourage an indigenous defense industry, developed a curious array of manufacturing and infrastructure-related industries. Protection from international and domestic competition, access to cheap government land and heavy subsidies of raw materials ensured a wide array of cushy jobs for military elites in 2020.

Data on Military’s Economic Influence

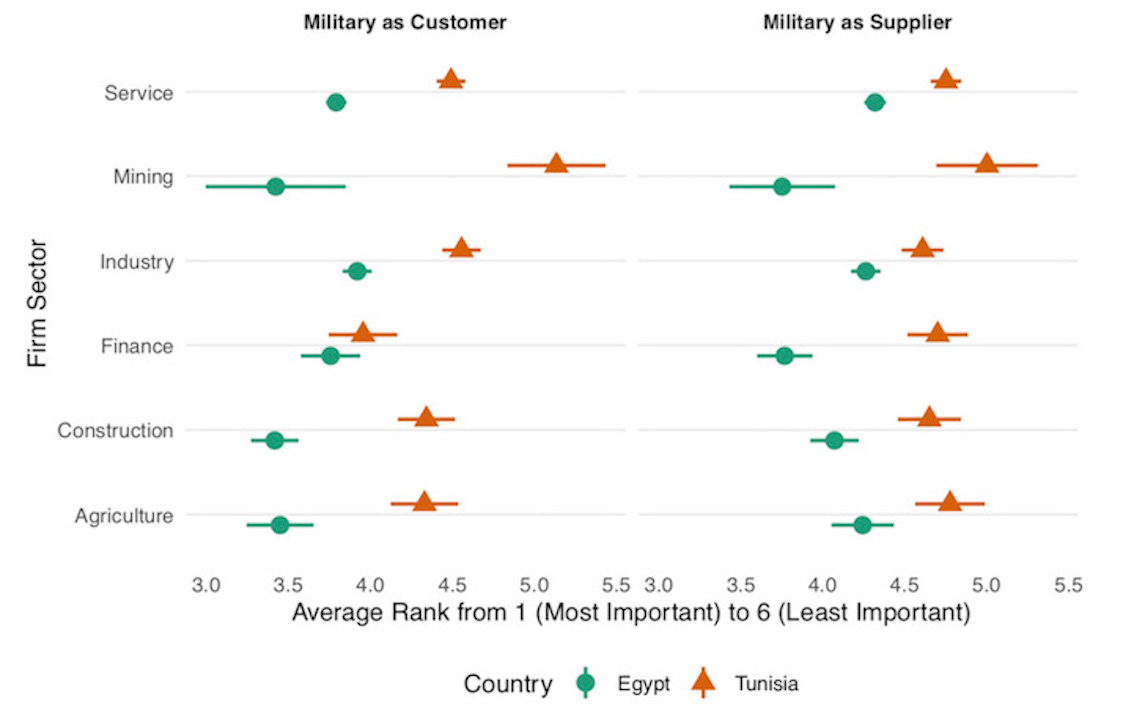

In my research into the political connections of Middle Eastern businesspeople, I wanted to understand just how strong the Egyptian military’s economic influence is. However, it is difficult to gain any hard numbers because the military can always protect information for “national security reasons.” Instead, I targeted online surveys at businesspeople in Egypt and Tunisia asking them to rank their suppliers of inputs and consumers of products. I included military-affiliated companies along with more common options like export markets, consumers and state-owned enterprises. The plot below shows survey data from 2017 from which I calculated the average rank (where 1 is the highest possible rank) for military-affiliated companies across a range of industries. Tunisia’s data is included as a reference point.

Average Rank of Military-Affiliated Companies to Business Respondents

SOURCE: Robert Kubinec. “Politically-Connected Firms and the Military-Clientelist Complex in North Africa.” SocArxiv, June 10, 2021, https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/mrfcu/

Egypt and Tunisia are often compared, with observers noting the much larger level of influence of the military in politics in Egypt. The plot above shows average ranks from respondents in the survey as dots with the plausible range of values due to sampling uncertainty as horizontal lines. The military is often a full rank more important supplier (right-hand side) or consumer (left-hand side) to businesses in Egypt (green dot) than in Tunisia (orange triangle). The military’s strongest presence in Egypt is in the mining sector, where it is approximately the third-most important supplier and consumer for companies. It also has a large presence in construction and agriculture as a customer and supplier, though its role as a customer is more significant. Even in the service sector, in which the weight of the military is relatively less, the Egyptian military has an outsize presence compared to its counterpart in Tunisia.

As Yezid Sayigh argued, the Egyptian military does not dominate the entire economy in the sense of accounting for a majority of gross domestic product. More conventional economic actors like consumers and export markets remain more important to Egyptian business, as we would expect. However, at the same time, military-affiliated businesses are far more involved in the economy than comparable countries, and this level of intervention is high enough to be measured solely through its displacement of private business and state-owned enterprises as suppliers and consumers. Furthermore, this intervention can be seen across sectors we might not anticipate based on defense needs alone, such as agriculture, finance and service industries.

I followed up this research with another survey targeted directly at Egyptian military personnel as part of a larger research project with Sharan Grewal. While the responses cannot be fully validated due to confidentiality concerns, I believe this information is some of the best evidence directly from military personnel. This survey recruited 1,314 personnel, of whom 496 reported a rank higher than corporal. Approximately 14 percent of these respondents reported spending at least some time working for a military-affiliated company, amounting to on average 24 percent of their work day. We also asked personnel about their retirement plans. For officers at the rank of second lieutenant level and above, 30 percent reported a desire to work in a military-affiliated company versus 21 percent in government and 25 percent in a private company. As such, while these enterprises may not dominate economic activity in the country, they are clearly a popular and powerful incentive for Egyptian officers to support the regime.

Implications

This increasing capture of economic activities by the Egyptian military has consequences for economic development and the survival of the regime. The enmeshment of military-affiliated companies in what were relatively mundane consumer and supplier relationships means that previously a-political economic transactions now increasingly require acquiescence from the regime. During my field research in Egypt in 2016, a factory owner who had previously participated in party politics explained he could no longer do so because his factory’s supplies came from a military-affiliated company, and without them he could not turn a profit. As a result, even though President al-Sisi’s regime has largely fallen short of promises to revive the economy, businesspeople face serious consequences if they choose to back an alternative or even criticize his policies in public. While investment and economic growth suffer, this stranglehold on elites outside the regime helps al-Sisi maintain power and suppress dissent.

Robert Kubinec, an assistant professor of political science at New York University-Abu Dhabi, is writing a book manuscript on the influence of powerful business interests on democratization in Egypt and Tunisia. His work on Middle East political economy, especially in Tunisia and Egypt, has appeared recently in the journals Political Analysis and Social Science Quarterly.