Country Profiles

LEBANON

Basic Data

HEADS OF STATE WITH

A MILITARY BACKGROUND

A MILITARY BACKGROUND

4 of 13

(as of 2020)

Excluding interim/acting

appointments

Excluding interim/acting

appointments

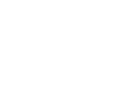

Total Military Personnel

ACTIVE

Source: Lebanese Armed Forces, via Aram Nerguizian, 2020.

Index Results

Scores on a scale of 1–5

Context

Lebanon’s cross-confessional composition shapes civil-military relations. Overlapping domestic and foreign conflicts heighten sectarian-political competition and limit the military’s role in matters of national defense and internal stability. This pattern of civil-military relations is the legacy of the brief civil war in 1958. In the aftermath, the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) intelligence branch sought to regulate political life, but confessional elites defeated a military-backed government in the 1970 presidential elections and the 1975–1990 civil war fragmented the LAF along sectarian lines.

The LAF has had to mitigate internal threats to national stability while struggling to deter Israel and Syria as external national security threats. The 1989 Taif Agreement ended the civil war, but militia disarmament and demobilization remain incomplete and the Shia Muslim paramilitary group Hezbollah maintains a parallel military force and continues military activities against Israel.

After the 1975–1990 civil war, Syria maintained an extensive military and intelligence presence in Lebanon, and the two countries signed a brotherhood treaty in 1991 that asserted Syrian suzerainty over Lebanese defense and foreign policy. Until the withdrawal of Syrian military and intelligence forces in 2005, this relegated the LAF to a constabulary role. The LAF has sought to reclaim its national security credentials since, but the continued endorsement of Hezbollah’s activities undermines this effort.

Since 2005, sectarian-political parties that once fought on the battlefield have fought through the ballot box and clientelist networks. These parties prefer that the LAF not evolve into an institution that can check their autonomy, resulting in a cycle of civil-military mistrust and chronic under-resourcing of the military. Despite these challenges, United States–led military assistance since 2006 has enabled the LAF to evolve into a credible partner in the fight against the self-proclaimed Islamic State, and to remain Lebanon’s most trusted state institution, with broad cross-confessional, public support.

The LAF has had to mitigate internal threats to national stability while struggling to deter Israel and Syria as external national security threats. The 1989 Taif Agreement ended the civil war, but militia disarmament and demobilization remain incomplete and the Shia Muslim paramilitary group Hezbollah maintains a parallel military force and continues military activities against Israel.

After the 1975–1990 civil war, Syria maintained an extensive military and intelligence presence in Lebanon, and the two countries signed a brotherhood treaty in 1991 that asserted Syrian suzerainty over Lebanese defense and foreign policy. Until the withdrawal of Syrian military and intelligence forces in 2005, this relegated the LAF to a constabulary role. The LAF has sought to reclaim its national security credentials since, but the continued endorsement of Hezbollah’s activities undermines this effort.

Since 2005, sectarian-political parties that once fought on the battlefield have fought through the ballot box and clientelist networks. These parties prefer that the LAF not evolve into an institution that can check their autonomy, resulting in a cycle of civil-military mistrust and chronic under-resourcing of the military. Despite these challenges, United States–led military assistance since 2006 has enabled the LAF to evolve into a credible partner in the fight against the self-proclaimed Islamic State, and to remain Lebanon’s most trusted state institution, with broad cross-confessional, public support.

Key Points

- The LAF is representative in cross-confessional terms and recognizes civilian authority, but the sectarian, clientelist political system generates confessional tensions and risks politicizing LAF operations.

- The military is risk averse and prefers political neutrality, but Lebanon’s competing sectarian-political parties limit military development to keep the LAF from challenging their political and economic autonomy.

- The LAF cultivates a nonsectarian corporate identity, enjoys high public trust, seeks to integrate women, and sees civil-military cooperation as critical to its success.

- Low capital spending on defense limits capabilities development and military professionalization, and transparency in defense spending is limited, but the LAF does not engage in large-scale commercial activities.

- Competing sectarian-political parties and a lack of defense expertise among Lebanese civilians cripple national defense policy making, and the LAF is more comfortable dealing with military and civilian personnel from donor countries.

Institutional Stability

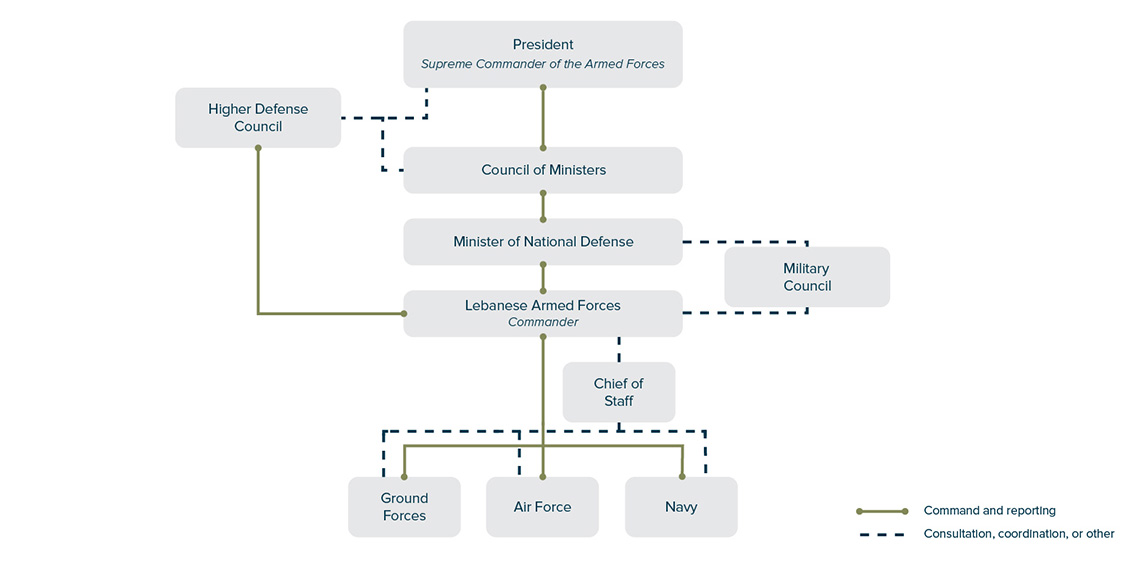

Founded on the principle of institutional control by elected civilian officials, the LAF sees itself as the protector of a civilian republic, not a vanguard of a regime, party, or faction. Law places the LAF at the disposal of the president and stipulates that the Council of Ministers determines public defense and security policy. Based on this, the Higher Defense Council, composed of civilian government officials, makes national defense decisions and adjudicates defense budget requests. Once the Higher Defense Council gives strategic direction, LAF Command has effective operational control, while the Ministry of Defense exercises minimal oversight at a distance.

The LAF interprets its constitutional role as intertwined with preserving Lebanon’s cross-confessional character. Military commanders have been known to reinterpret or fail to implement government directives that pose a risk to the cross-confessional power balance, and Lebanon’s six largest communities are, by custom, permanently represented on the Military Council.

Civilian and military leaders regularly discuss the defense budget, military acquisition, major mission areas, and appointments of brigade commanders, deputy chiefs of staff, or Military Council members. LAF Command draws up internal planning, procurement, budgeting, and recruitment assumptions, which senior government officials vet.

The post–civil war LAF has preferred to defer public order roles to civilian security agencies, but the LAF’s high level of public trust leads to mission creep and overlap, causing public confusion about jurisdiction on matters tied to public order, internal stability operations, and counterterrorism coordination. These missions fall outside the scope of the LAF’s primary territorial defense mission.

From 1990 to 2005, the Syrian security apparatus in Lebanon curtailed the LAF’s territorial defense role, but the LAF began to resume this role with the departure of Syrian intelligence and military forces in 2005 and the resumption of international military assistance. The 2006 Israel-Hezbollah conflict, 2007 counterterrorism operations in the Nahr el-Bared Palestinian refugee camp, and the 2017 counter-Islamic State campaign accelerated this process. The armed forces now actively coordinate missions and priorities with civilian security agencies through formal channels such as the Higher Defense Council.

The jurisdiction of civilian and military courts are generally separate, but civilians continue to be tried for national security offenses in military courts. The military recognizes the moral hazard this presents, but military courts report to the minister of defense, so they fall outside the LAF chain of command. Likewise, the military judicial system sometimes tries military personnel for civil or criminal offenses. This is a declining trend, especially considering growing public awareness and scrutiny of the military, and the military’s sensitivity to maintaining popular support.

The LAF interprets its constitutional role as intertwined with preserving Lebanon’s cross-confessional character. Military commanders have been known to reinterpret or fail to implement government directives that pose a risk to the cross-confessional power balance, and Lebanon’s six largest communities are, by custom, permanently represented on the Military Council.

Key Legal Documents

- Decree No. 102 of 1983, The National Defense Law, is the main law that governs the military

- Constitution, Article 64, assigning the prime minister as vice president of the Higher Defense Council

- Constitution, Article 65, subordinating the armed forces to the Council of Ministers

Civilian and military leaders regularly discuss the defense budget, military acquisition, major mission areas, and appointments of brigade commanders, deputy chiefs of staff, or Military Council members. LAF Command draws up internal planning, procurement, budgeting, and recruitment assumptions, which senior government officials vet.

The post–civil war LAF has preferred to defer public order roles to civilian security agencies, but the LAF’s high level of public trust leads to mission creep and overlap, causing public confusion about jurisdiction on matters tied to public order, internal stability operations, and counterterrorism coordination. These missions fall outside the scope of the LAF’s primary territorial defense mission.

From 1990 to 2005, the Syrian security apparatus in Lebanon curtailed the LAF’s territorial defense role, but the LAF began to resume this role with the departure of Syrian intelligence and military forces in 2005 and the resumption of international military assistance. The 2006 Israel-Hezbollah conflict, 2007 counterterrorism operations in the Nahr el-Bared Palestinian refugee camp, and the 2017 counter-Islamic State campaign accelerated this process. The armed forces now actively coordinate missions and priorities with civilian security agencies through formal channels such as the Higher Defense Council.

The jurisdiction of civilian and military courts are generally separate, but civilians continue to be tried for national security offenses in military courts. The military recognizes the moral hazard this presents, but military courts report to the minister of defense, so they fall outside the LAF chain of command. Likewise, the military judicial system sometimes tries military personnel for civil or criminal offenses. This is a declining trend, especially considering growing public awareness and scrutiny of the military, and the military’s sensitivity to maintaining popular support.

Political System

Hezbollah

Former Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) deputy chief of staff for plans Brigadier General Maroun Hitti described LAF-Hezbollah relations as “case-by-case interest-based deconfliction.” LAF Command and the Directorate of Military Intelligence actively deconflict with Hezbollah at the strategic level as needed, an anomalous feature of Lebanon’s post–civil war political settlement. The dynamics resulting from this settlement have seen ebbs and flows in the legitimacy of Hezbollah, a Shia paramilitary and political organization, and the LAF, a confessionally representative national security institution.

The 1989 Ta’if Agreement that ended the civil war legitimized Hezbollah’s armed status under the guise of “resistance” against Israeli occupation of Lebanese territory, with the support of Syria and its international sponsor, Iran. In parallel, Syria’s intelligence apparatus relegated the postwar Lebanese military to a constabulary role, serving Syrian interests.

The departure of Syria’s intelligence and military apparatus in 2005 disrupted Hezbollah’s disproportionate influence on national security decisionmaking and saw the gradual rehabilitation of the LAF’s national security legitimacy. Aided by international military assistance from the United States and other partners, the LAF has attempted to develop, deepen, and maintain its military credibility and autonomy. Despite these institutional gains, the LAF cannot ignore Hezbollah, which has maintained its preeminence among a significant cross-section of Lebanon’s Shia population. So long as Hezbollah commands this support, the LAF and Hezbollah have little choice but to maintain cool yet cordial ties, often despite serious interorganizational tensions.

The 1989 Ta’if Agreement that ended the civil war legitimized Hezbollah’s armed status under the guise of “resistance” against Israeli occupation of Lebanese territory, with the support of Syria and its international sponsor, Iran. In parallel, Syria’s intelligence apparatus relegated the postwar Lebanese military to a constabulary role, serving Syrian interests.

The departure of Syria’s intelligence and military apparatus in 2005 disrupted Hezbollah’s disproportionate influence on national security decisionmaking and saw the gradual rehabilitation of the LAF’s national security legitimacy. Aided by international military assistance from the United States and other partners, the LAF has attempted to develop, deepen, and maintain its military credibility and autonomy. Despite these institutional gains, the LAF cannot ignore Hezbollah, which has maintained its preeminence among a significant cross-section of Lebanon’s Shia population. So long as Hezbollah commands this support, the LAF and Hezbollah have little choice but to maintain cool yet cordial ties, often despite serious interorganizational tensions.

The LAF struggles to balance accommodating Lebanon's sectarian politics with sustaining military professionalization. Competing sectarian-political elites have deprioritized military development and limited the military to internal and constabulary roles, to prevent the LAF from undermining elites’ political and economic autonomy. LAF Command makes career and competence-based selections for posts up to regimental commanders, but has less flexibility in selecting deputy chiefs of staff and brigade commanders. The selection of a new LAF commander can also take on divisive political overtones among sectarian-political elites, often resulting in a compromise appointment.

The LAF has sought to strengthen its corporate identity in the face of self-serving, clientelistic behavior among civilian authorities. Military cohesion is by no means uniform, but the LAF has become one of Lebanon’s most professional national institutions, in large part because of Western security assistance.

With its own chain of command and close coordination with Iran, the paramilitary group Hezbollah poses a long-term challenge for Lebanese military politics. Hezbollah enjoys broad popular support among its predominantly Shia Muslim constituency, which often forces the LAF to accommodate the group’s political preferences. This is not unlike the LAF’s approach to other factions that, like Hezbollah, also maintain irregular forces.

LAF Social Media Engagement

Twitter

Twitter

Tweets

4,541

4,541

Followers

392,403

392,403

Listed

323

323

Facebook

Facebook

Likes

305,316

305,316

Followers

312,357

312,357

Talked About

34,766

34,766

Youtube

Youtube

Uploads

328

328

Subscribers

17,700

17,700

Video Views

4,351,743

4,351,743

The LAF does not dominate political space, although it enjoys strong cross-confessional support. It is not focused on maintaining the incumbent political order, and seeks to remain neutral in the face of public debate and political change so long as these take place peacefully. Public debate on defense affairs is generally permitted, but a lack of information and poor responsiveness from the LAF and sectarian-political elites often impedes this. The public policy community actively discusses the budget, and defense analysts are not discouraged from asking the LAF or the government tough questions about defense finances.

Nation Building and Citizenship

Cohesion in the Armed Forces

Several factors contribute to the cohesion of the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF), while accommodating the country’s multi-confessional character. The first is esprit de corps. LAF personnel take pride in belonging to one of Lebanon’s few functioning and respected state institutions, underpinning a shared sense of belonging and corporate loyalty. This is especially strong among elite special forces units, and military personnel who flout norms of loyalty risk social ostracization.

A second factor contributing to cohesion is the expectation of a life-long connection to the military. An unblemished military career with high visibility and sufficient longevity often translates into professional and possibly political opportunities after retirement. As a result, informal violations of the military’s norms and expectations of behavior, even when these do not break the law, can result in loss of stability, entitlements, benefits, and post-career opportunities.

Third, the LAF’s cross-confessional character is a source of cohesion in peace time but of division in times of crisis. After the 1975‒1990 civil war, the LAF became a force that was more representative and that saw more confessional mixing across units. This contributed to high public trust, but cross-confessional tensions and violence in wider society continue to strain LAF cohesion and unity.

The quality of military leadership can determine how these factors interact to strengthen or weaken cohesion. After the withdrawal of Syrian forces from Lebanon in 2005, Lebanese sectarian-political elites sought to penetrate and influence military appointments and promotions to keep senior officers from challenging them. This has often led to the appointment of senior officers who can sustain LAF cohesion, but not make the LAF cohesive enough that it is no longer susceptible to sectarian-political competition.

A second factor contributing to cohesion is the expectation of a life-long connection to the military. An unblemished military career with high visibility and sufficient longevity often translates into professional and possibly political opportunities after retirement. As a result, informal violations of the military’s norms and expectations of behavior, even when these do not break the law, can result in loss of stability, entitlements, benefits, and post-career opportunities.

Third, the LAF’s cross-confessional character is a source of cohesion in peace time but of division in times of crisis. After the 1975‒1990 civil war, the LAF became a force that was more representative and that saw more confessional mixing across units. This contributed to high public trust, but cross-confessional tensions and violence in wider society continue to strain LAF cohesion and unity.

The quality of military leadership can determine how these factors interact to strengthen or weaken cohesion. After the withdrawal of Syrian forces from Lebanon in 2005, Lebanese sectarian-political elites sought to penetrate and influence military appointments and promotions to keep senior officers from challenging them. This has often led to the appointment of senior officers who can sustain LAF cohesion, but not make the LAF cohesive enough that it is no longer susceptible to sectarian-political competition.

The LAF has been a volunteer force since 2007. The government instituted compulsory military service as a means of rebuilding national and cross-confessional cohesion following the civil war, and thousands of military age males were conscripted for one year of service between 1990 and 2007. Conscription crossed demographic and confessional divides, but involved minimal training and resulted in a largely demoralized force, without imparting corporate identity. Since abandoning conscription, the LAF has become one of the most professional state institutions.

The public perceives the military as an honest broker and arbiter in times of national crisis, recognizing its representative confessional makeup and general reluctance to intervene in politics. However, the LAF’s attempts to maintain this neutrality in the face of protests sometimes lead to the perception that it supports one side or another. Civilians, particularly the media, are free to discuss the military or defense affairs, but self censorship often limits discussion and the military’s overclassification of data leaves the public and media somewhat ill-informed about defense affairs.

In addition to cross-confessional representation, the military has actively sought to integrate women. By 2019, the LAF had recruited some 4,000 women into its ranks, including personnel in military aviation (fixed and rotary), special forces, military intelligence, counterintelligence, and headquarters management. LAF Command may further integrate women into combat roles. However, changes in facilities, rules, and regulations have not kept pace with the recruitment of women, and there is no clear mechanism for dealing with sexual misconduct, nor does the LAF have a clear gender mainstreaming strategy.

The Lebanese military sees civil-military cooperation (CIMIC) as integral to the high levels of public trust in and support for the LAF, but a CIMIC center founded in 2014 has only slowly streamlined its activities into the military’s other functions. The military considers CIMIC critical to consolidating deployments in parts of the country that were military no-go zones under Syrian fiat from 1990 to 2005. External partners recognize this need and have assisted the LAF in staffing and developing its CIMIC directorate, and if given the opportunity, the LAF would prefer CIMIC be elevated to command by a deputy chief of staff, alongside personnel, operations, logistics, and planning.

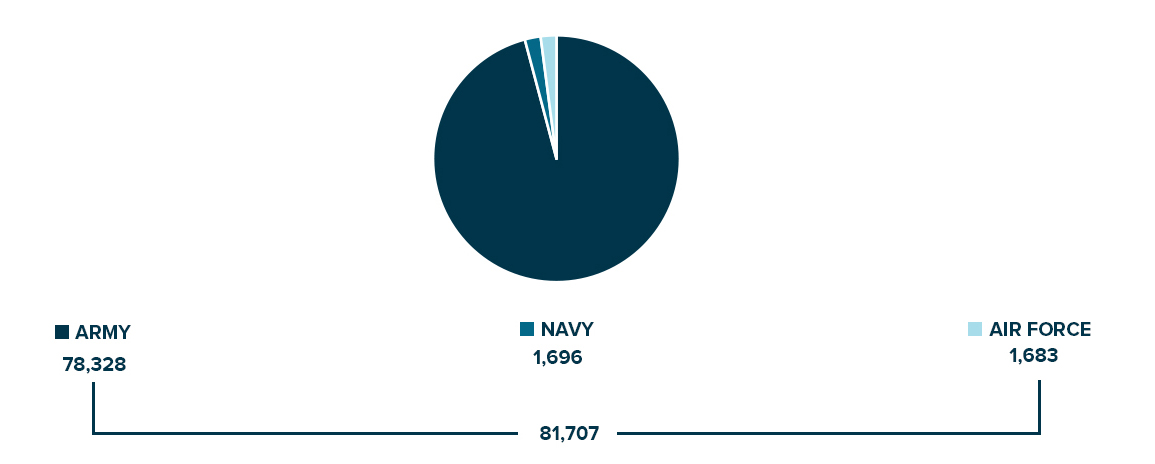

Active Military Personnel Versus Labor Force

Sources: Lebanese Armed Forces, via Aram Nerguizian, 2020. | U.S. Department of State

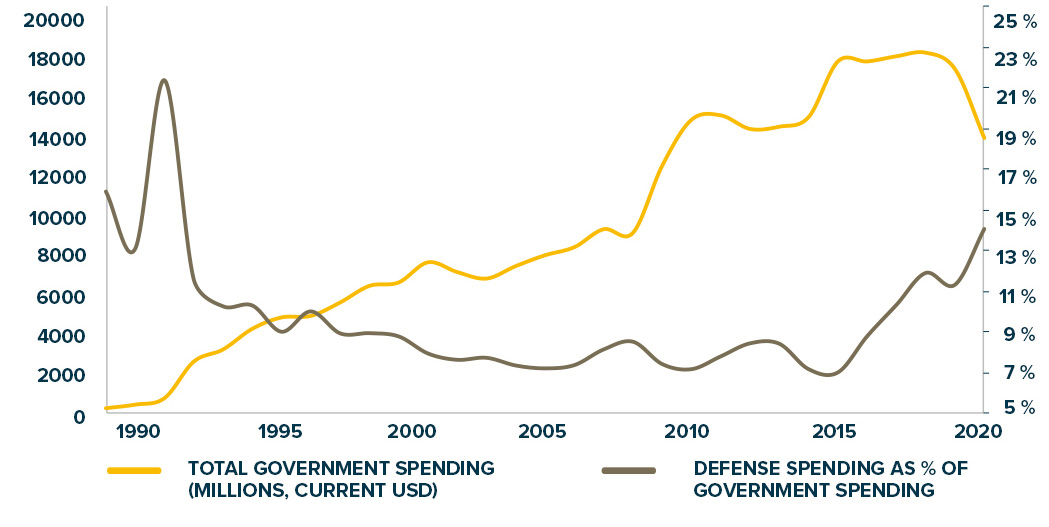

Budget and Economy

Lebanese defense spending proposals, like all elements of proposed national spending, make clear where funding goes at the top level, but budget details under this level remain internal to the LAF, the Ministry of Finance, and the government. Five-year Capabilities Development Plans, generated with the support of foreign partners, contain sections on budgeting that are granular, but these plans are not circulated widely or discussed publicly. LAF budget formulation procedures span its planning, personnel, operations, logistics, and intelligence branches. Once budget proposals make their way to the government they follow much the same vetting, justification, markup, and markdown processes that other agencies’ budgets undergo, in coordination with the Ministry of Finance.

Sectarian-political dynamics and the absence of a mechanism for developing and negotiating broad national defense needs limits funding for defense sector needs. The LAF does not broach the wider discussion of defense needs for fear of exacerbating confessional tensions. Civilian leaders—the president, prime minister, minister of finance, parliamentarians, and sectarian-political elites outside the government—favor maintaining current expenditures rather than approving capital expenditures that could augment the capabilities and professionalism of the military. However, once civilian leaders decide to accept foreign military aid, especially from Western nations, the LAF and the donor nation determine the trajectory of that aid. This reflects the general disinterest of sectarian-political elites in aid from which they may not benefit directly.

Transparency in defense spending is inconsistent. Extra-budgetary expenditures are uncommon, but in the absence of an official budget from 2005 to 2017 Parliament allocated funding directly to the LAF. The state’s central auditing agency, the Court of Audit, does not have a track record of submitting audit reports on state budgets, let alone defense budgets, although the LAF does coordinate with the Court on tenders and bids. Little legislation exists on corruption risks in defense procurement, and unlike civilian agencies, the LAF are exempted from the scrutiny of the Public Procurement Directorate. Instead, the LAF’s General Directorate for Administration manages defense procurement. On rare occasions, senior officers have asked for kickbacks to facilitate tenders or secure military contracts, but LAF Command has punished these personnel or Western contractors have rebuffed the attempts, in compliance with anti-corruption laws in their own countries.

The LAF engages only in small-scale commercial activities. There is little extra-budgetary income, and external aid is generally in-kind or spent in donor countries, as credit against which purchases are made. Cash transfers tied to aid or arms purchases are a declining feature of LAF funding. Military personnel rarely engage in public or private business ventures. This reflects the reality that Lebanon’s competing sectarian-political elites reserve that domain for themselves and their clientelist networks. The LAF owns a few private businesses that are open for civilian use, such as the Monroe Hotel in downtown Beirut, but the negligible revenues from these businesses are not revealed in a transparent way.

Sectarian-political dynamics and the absence of a mechanism for developing and negotiating broad national defense needs limits funding for defense sector needs. The LAF does not broach the wider discussion of defense needs for fear of exacerbating confessional tensions. Civilian leaders—the president, prime minister, minister of finance, parliamentarians, and sectarian-political elites outside the government—favor maintaining current expenditures rather than approving capital expenditures that could augment the capabilities and professionalism of the military. However, once civilian leaders decide to accept foreign military aid, especially from Western nations, the LAF and the donor nation determine the trajectory of that aid. This reflects the general disinterest of sectarian-political elites in aid from which they may not benefit directly.

Transparency in defense spending is inconsistent. Extra-budgetary expenditures are uncommon, but in the absence of an official budget from 2005 to 2017 Parliament allocated funding directly to the LAF. The state’s central auditing agency, the Court of Audit, does not have a track record of submitting audit reports on state budgets, let alone defense budgets, although the LAF does coordinate with the Court on tenders and bids. Little legislation exists on corruption risks in defense procurement, and unlike civilian agencies, the LAF are exempted from the scrutiny of the Public Procurement Directorate. Instead, the LAF’s General Directorate for Administration manages defense procurement. On rare occasions, senior officers have asked for kickbacks to facilitate tenders or secure military contracts, but LAF Command has punished these personnel or Western contractors have rebuffed the attempts, in compliance with anti-corruption laws in their own countries.

The LAF engages only in small-scale commercial activities. There is little extra-budgetary income, and external aid is generally in-kind or spent in donor countries, as credit against which purchases are made. Cash transfers tied to aid or arms purchases are a declining feature of LAF funding. Military personnel rarely engage in public or private business ventures. This reflects the reality that Lebanon’s competing sectarian-political elites reserve that domain for themselves and their clientelist networks. The LAF owns a few private businesses that are open for civilian use, such as the Monroe Hotel in downtown Beirut, but the negligible revenues from these businesses are not revealed in a transparent way.

Government and Defense Spending

Source: Lebanese Armed Forces, via Aram Nerguizian, 2020.

National Defense

The paucity of professional civilians in defense affairs leaves a considerable gap in the LAF’s ability to develop its capabilities and respond to national defense policy needs. Most civilians in defense are either politicians in leadership roles or political appointees from one of the sectarian-political clientelist networks. As a result, civilians involved in defense affairs lack a grasp of military capabilities, needs, or development goals, and have little incentive to close this knowledge gap.

Political agendas undermine critical aspects of Lebanese national defense planning and military development. Sectarian-political parties, which often enjoy more power and autonomy than state institutions, espouse competing foreign policy priorities, undermining coherent foreign policy formulation. This in turn hamstrings national defense policy making, force development, and defense budgeting. LAF effectiveness and efficiency are limited as a result, compelling it to seek out the “least bad common denominator” preferences and develop at least some of the capabilities it deems necessary to address national defense needs.

The Lebanese military has grown accustomed to civilians limiting capital expenditure, and civilian authorities rarely consider the need to reform personnel expenditures. This mutual apathy for reform, on the part of both civilians and military officers, endangers the long-term professionalization and capabilities development of the LAF by disconnecting available resources from realistic strategic objectives.

The LAF likewise tends to fill capability and future force planning gaps by relying on military personnel instead of developing the competence of civilians who could act as an institutional memory for the force. There is less turnover in civilian positions than military ones and military personnel take knowledge of effective practices and procedures with them when they leave a position. In addition, civilian officials are generally uninterested in what few opportunities exist for training in defense affairs abroad, and many do not believe that such courses would benefit their careers. When the LAF has turned to Lebanese civilians, it has most often done so in areas such as civil-military cooperation, public diplomacy, or information operations, areas that are important, but not critical, to combat operations.

In strategic planning, procurement, and financial management, the LAF is far more comfortable dealing with donor or partner-supported civilians on a short term or limited basis than it is in hiring full time Lebanese civilian defense professionals. For example, the Rapid Land Border Project, put into place after 2010, employed UK-funded foreign civilian and retired military experts to plan for and execute the LAF’s northern and eastern border security requirements. The absence of a competent and empowered cadre of civilian defense professionals and senior civilian officials at the ministerial level undermines structural reform of decisionmaking that the LAF cannot, or will not, pursue in a vacuum, and leaves national defense strategy less coherent.

Political agendas undermine critical aspects of Lebanese national defense planning and military development. Sectarian-political parties, which often enjoy more power and autonomy than state institutions, espouse competing foreign policy priorities, undermining coherent foreign policy formulation. This in turn hamstrings national defense policy making, force development, and defense budgeting. LAF effectiveness and efficiency are limited as a result, compelling it to seek out the “least bad common denominator” preferences and develop at least some of the capabilities it deems necessary to address national defense needs.

The Lebanese military has grown accustomed to civilians limiting capital expenditure, and civilian authorities rarely consider the need to reform personnel expenditures. This mutual apathy for reform, on the part of both civilians and military officers, endangers the long-term professionalization and capabilities development of the LAF by disconnecting available resources from realistic strategic objectives.

The LAF likewise tends to fill capability and future force planning gaps by relying on military personnel instead of developing the competence of civilians who could act as an institutional memory for the force. There is less turnover in civilian positions than military ones and military personnel take knowledge of effective practices and procedures with them when they leave a position. In addition, civilian officials are generally uninterested in what few opportunities exist for training in defense affairs abroad, and many do not believe that such courses would benefit their careers. When the LAF has turned to Lebanese civilians, it has most often done so in areas such as civil-military cooperation, public diplomacy, or information operations, areas that are important, but not critical, to combat operations.

In strategic planning, procurement, and financial management, the LAF is far more comfortable dealing with donor or partner-supported civilians on a short term or limited basis than it is in hiring full time Lebanese civilian defense professionals. For example, the Rapid Land Border Project, put into place after 2010, employed UK-funded foreign civilian and retired military experts to plan for and execute the LAF’s northern and eastern border security requirements. The absence of a competent and empowered cadre of civilian defense professionals and senior civilian officials at the ministerial level undermines structural reform of decisionmaking that the LAF cannot, or will not, pursue in a vacuum, and leaves national defense strategy less coherent.

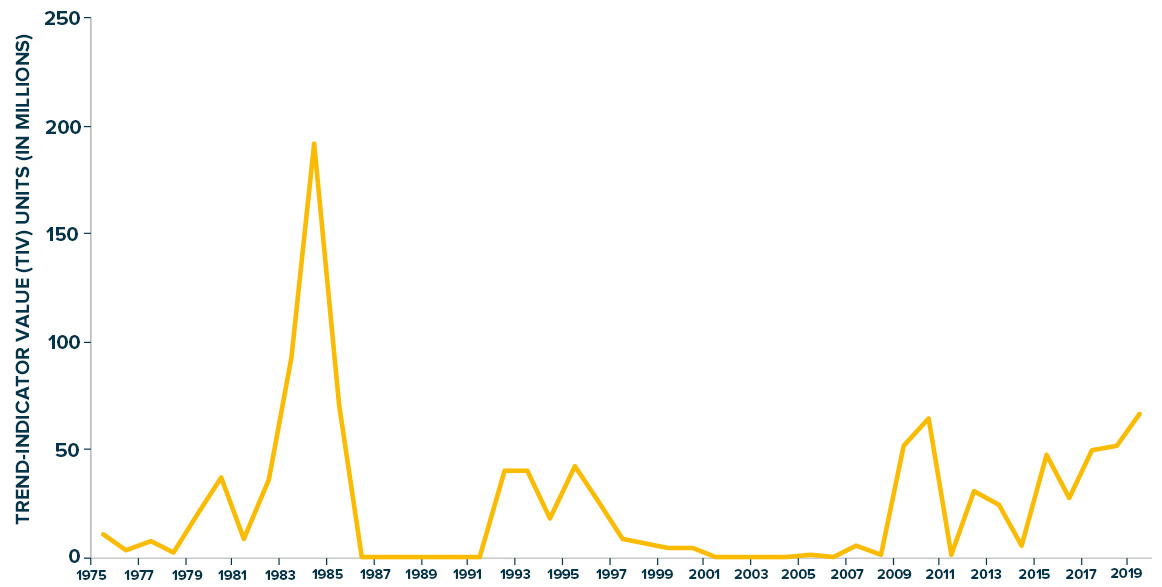

Arms Imports

Note: The TIV is a unit of measure developed by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) to calculate the volume of international transfers of major conventional weapons. It does not represent actual prices and cannot be directly compared with figures for GDP or military spending.

Source: SIPRI