Country Profiles

TUNISIA

Basic Data

HEADS OF STATE WITH

A MILITARY BACKGROUND

A MILITARY BACKGROUND

1 of 6

(as of 2020)

Excluding interim/acting

appointments

Excluding interim/acting

appointments

Index Results

Scores on a scale of 1–5

Context

Tunisian civil-military relations are stable. Independence was the result of political, not military, struggle, and foreign relations have been relatively peaceful since. Aside from a bloody but brief clash with France over control of the Bizerte naval base in 1961, Tunisia has not engaged in military conflict with other states. Tunisia is friendly to the West and Tunisian officers train in the United States and France, and Tunisia’s foreign policy orientation does not heighten the political importance of the armed forces.

The Tunisian Armed Forces (TAF) have maintained political neutrality. They returned to the barracks after a confrontation with Libya-backed insurgents in Gafsa in 1980 and a campaign of terrorist attacks following the 2011 transition toward democracy. Tunisian officers harbor a sense of exceptionalism against triggering coups, due in large part to the TAF’s marginal role in the rise of founding president Habib Bourguiba.

Internal and external political dynamics pose challenges to the stability of Tunisian civil-military relations. An Islamist insurgency in the western borderlands, near Mount Chaambi, has endured for years. Ongoing socioeconomic challenges also generate political tension and threaten loss of faith in democracy, as evidenced by Tunisia being the largest exporter of Islamist militants to Syria after 2011.

Externally, Libya has been a constant source of worry, especially since 2014, with expanding cross-border smuggling and an increasing risk of weapons being used that could threaten Tunisian stability. These internal and external political dynamics have prompted a surge in U.S. and European security assistance since 2011, resulting in unprecedented external support but prioritizing donors’ two main agendas: countering terrorism and controlling migration.

The Tunisian Armed Forces (TAF) have maintained political neutrality. They returned to the barracks after a confrontation with Libya-backed insurgents in Gafsa in 1980 and a campaign of terrorist attacks following the 2011 transition toward democracy. Tunisian officers harbor a sense of exceptionalism against triggering coups, due in large part to the TAF’s marginal role in the rise of founding president Habib Bourguiba.

Internal and external political dynamics pose challenges to the stability of Tunisian civil-military relations. An Islamist insurgency in the western borderlands, near Mount Chaambi, has endured for years. Ongoing socioeconomic challenges also generate political tension and threaten loss of faith in democracy, as evidenced by Tunisia being the largest exporter of Islamist militants to Syria after 2011.

Externally, Libya has been a constant source of worry, especially since 2014, with expanding cross-border smuggling and an increasing risk of weapons being used that could threaten Tunisian stability. These internal and external political dynamics have prompted a surge in U.S. and European security assistance since 2011, resulting in unprecedented external support but prioritizing donors’ two main agendas: countering terrorism and controlling migration.

Key Points

- The TAF operates exclusively under the control of civilian political leaders, promoting a clear division of labor with internal security forces and professional values that reinforce this control.

- The TAF does not engage in politics, a stance reinforced by a republican tradition of avoiding coups, largely apolitical command appointments, and openness to public discussion of defense affairs..

- Tunisians view the military as having a positive influence on nation building, but the TAF also suffers from a perception of regional favoritism and low compliance with conscription.

- The transparency of defense finances has increased substantially since 2011, corruption risk is low by the standards of the region, and the military does not intervene in setting national economic policy.

- A pre-2011 legacy of coup-proofing reduces the ability of the TAF to perform its national defense mission, but it has made strides in planning, resourcing, and human resource management.

Institutional Stability

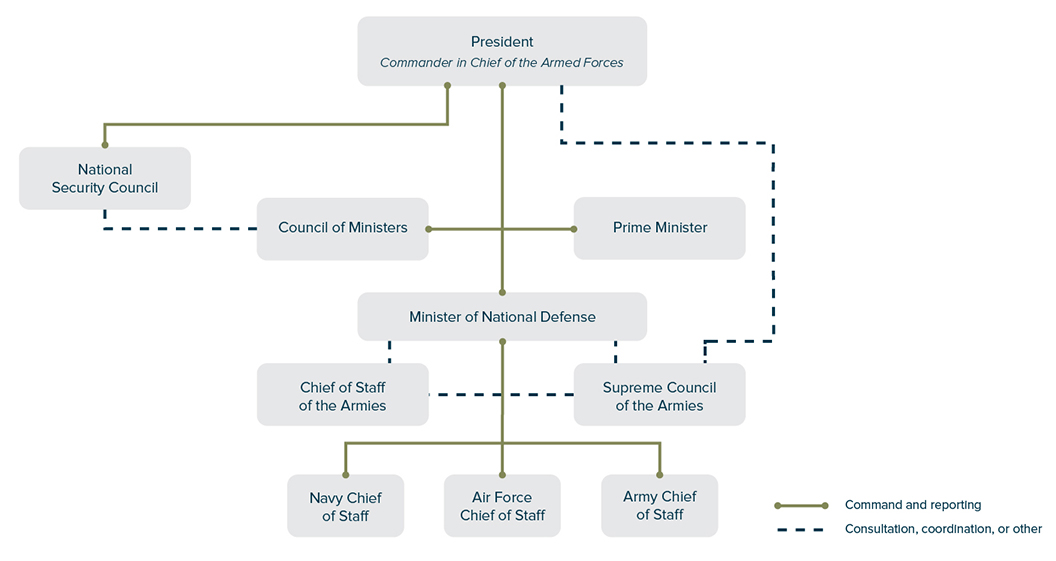

The Tunisian Constitution assigns no special status to the armed forces, but gives the state alone the right to establish a military, and requires the military to remain politically neutral. By both law and established practice, the Tunisian military is under the full control of the executive. The armed forces do not answer to any informal authority or political party, nor do they have parallel missions different from the ones assigned to them. The TAF does not operate as a rogue political actor, nor is there evidence that its budget is secretive or that the TAF creates friction in relations between civilian and military leaders.

Legally constituted civilian authorities—the president, the Council of Ministers, and minister of defense—are in command of the armed forces. TAF commanders do not enter politics, and civilian leaders, led by the president, set the country’s defense policy, while consulting the TAF on technical affairs. The military is not a decisionmaker in its own right, and the minister of defense is always a civilian.

A National Security Council was created in 1990 and reorganized in 2017, and convenes at least once a quarter to discuss national security affairs. It is headed by the president, who has the power to convene the council whenever the need arises. The prime minister; ministers of defense, justice, foreign affairs, and finance; and the speaker of Parliament also sit on the National Security Council. The council may invite TAF generals to attend meetings, but is not legally obliged to do so.

Tunisia has not published a national security strategy to date, due to an absence of baseline documents against which to make strategic assessments, an overreliance on informal interactions in decisionmaking, and a lack of civilian expertise with which to conduct strategic reviews. The armed forces also lack a chief of staff to coordinate between the different services. These dysfunctional aspects of Tunisian defense planning weaken the ability to identify and address defense needs.

The TAF does not interfere in the work of civilian authorities. It plays no role in the economy of the country, and there are no reports of encroachment or conflict between the military courts and their civilian counterparts. The respective roles of the armed forces and internal security forces under the control of the Ministry of Interior are clear. Fighting terrorism falls to the Ministry of Interior and its Brigades Anti-Terrorisme, while the military lends support. Coordination has been effective in reducing duplication of effort and waste, and has enhanced Tunisian counterinsurgency on the western border with Algeria and counterterrorism operations in the interior of the country.

Legally constituted civilian authorities—the president, the Council of Ministers, and minister of defense—are in command of the armed forces. TAF commanders do not enter politics, and civilian leaders, led by the president, set the country’s defense policy, while consulting the TAF on technical affairs. The military is not a decisionmaker in its own right, and the minister of defense is always a civilian.

Key Legal Documents

- Constitution, Article 77, establishing presidential powers in national defense

- Order 735 of 1979, last amended by Order 4209 of 2014, organizing the Ministry of National Defense and the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces

- Order 70 of 2017, detailing the role, structure, activities, decisions, and budget of the National Security Council

- Presidential Resolution of 30 October 2017, establishing security committees of the National Security Council

A National Security Council was created in 1990 and reorganized in 2017, and convenes at least once a quarter to discuss national security affairs. It is headed by the president, who has the power to convene the council whenever the need arises. The prime minister; ministers of defense, justice, foreign affairs, and finance; and the speaker of Parliament also sit on the National Security Council. The council may invite TAF generals to attend meetings, but is not legally obliged to do so.

Tunisia has not published a national security strategy to date, due to an absence of baseline documents against which to make strategic assessments, an overreliance on informal interactions in decisionmaking, and a lack of civilian expertise with which to conduct strategic reviews. The armed forces also lack a chief of staff to coordinate between the different services. These dysfunctional aspects of Tunisian defense planning weaken the ability to identify and address defense needs.

The TAF does not interfere in the work of civilian authorities. It plays no role in the economy of the country, and there are no reports of encroachment or conflict between the military courts and their civilian counterparts. The respective roles of the armed forces and internal security forces under the control of the Ministry of Interior are clear. Fighting terrorism falls to the Ministry of Interior and its Brigades Anti-Terrorisme, while the military lends support. Coordination has been effective in reducing duplication of effort and waste, and has enhanced Tunisian counterinsurgency on the western border with Algeria and counterterrorism operations in the interior of the country.

Political System

Impact of the Libyan Civil War

Threats from Libya have long influenced the threat perception and force development of the Tunisian Armed Forces (TAF). The 1981 “Qafsa Incident,” in which Libya funded and trained an attempted militant takeover of a Tunisian mining town, spurred modernization. A renewed focus on containing the spillover effects of armed conflict, smuggling, and terrorism from Libya since 2011 has resulted in a hardening of the border, drawing the TAF into border policing and law enforcement roles for which it is ill-prepared in terms of doctrine and training.

This intensified border role has also thrust into sharper relief longstanding problems of information sharing and deconfliction between the TAF and Ministry of Interior agencies, in particular the National Guard, the country’s main constabulary force. TAF border operations have convinced many senior Tunisian officers that the military should not be the only, or even the primary, means of addressing cross-border challenges from Libya. Instead, they assert, the country needs a holistic policy of socioeconomic development and political inclusion.

The diverse array of threats from Libya—low-intensity, asymmetric threats like terrorism and smuggling and, after the eruption of the 2019 civil war in the Tripoli region, high-end threats like drones and fixed-wing aircraft—confront the Tunisian military with choices about future procurement. However, the planning and budgetary process, with input and oversight from civilians, remains hobbled by capacity shortfalls, bureaucratic barriers, and distrust between the military and parliamentary oversight committees.

The internationalization of Libya’s war also strains Tunisia’s policy of neutrality and “equidistance” on Libya, and sharpens fault lines among Tunisian elites, including military officers, who back rival sides in the Libyan conflict. The Tunisian military has remained admirably aloof and nonpartisan on these rivalries, though that may come under increasing pressure given the growing involvement of Turkey and the United Arab Emirates.

This intensified border role has also thrust into sharper relief longstanding problems of information sharing and deconfliction between the TAF and Ministry of Interior agencies, in particular the National Guard, the country’s main constabulary force. TAF border operations have convinced many senior Tunisian officers that the military should not be the only, or even the primary, means of addressing cross-border challenges from Libya. Instead, they assert, the country needs a holistic policy of socioeconomic development and political inclusion.

The diverse array of threats from Libya—low-intensity, asymmetric threats like terrorism and smuggling and, after the eruption of the 2019 civil war in the Tripoli region, high-end threats like drones and fixed-wing aircraft—confront the Tunisian military with choices about future procurement. However, the planning and budgetary process, with input and oversight from civilians, remains hobbled by capacity shortfalls, bureaucratic barriers, and distrust between the military and parliamentary oversight committees.

The internationalization of Libya’s war also strains Tunisia’s policy of neutrality and “equidistance” on Libya, and sharpens fault lines among Tunisian elites, including military officers, who back rival sides in the Libyan conflict. The Tunisian military has remained admirably aloof and nonpartisan on these rivalries, though that may come under increasing pressure given the growing involvement of Turkey and the United Arab Emirates.

The military is not beholden to a specific party, ideology, or ruling elite. It belongs to the state, and by extension the nation, and executes legally received orders. The military deployed during urban bread riots in late 1983 and early 1984, and in response to an uprising in Gafsa in 2008. The TAF obeyed Ben Ali's orders to deploy during the 2011 uprising, during which the TAF did not fire on civilians, and the TAF has since been ordered to support Ministry of Interior operations against terrorist cells in the western borderlands. Military officers, now as then, do not perceive themselves as partisan actors on such occasions.

A disproportionate number of officers prior to 2011 were from the Sahel, or coast, home to Bourguiba and Ben Ali, but this did not make Tunisian officers integral members of the ruling elite. Military officers from the Sahel did not play a major role in choosing Bourguiba and Ben Ali, who engaged in coup-proofing activities while in office. State agencies did not sponsor militias or other armed forces outside the military chain of command, but Bourguiba relied on the police and his ruling party as the main pillars of his rule, while Ben Ali fostered mistrust between internal security and intelligence agencies and the military to strengthen his hold on power. Relations between the military and the police have gradually improved since 2011, especially in cooperating against Islamist terrorism and insurgency.

Military command appointments are not overly politicized. Senior Tunisian officers are selected on professional criteria and are generally well-trained and competent, and the TAF is not factionalized along ideological or communal lines. The military education system promotes civilian oversight and obedience to legal authority. Many Tunisian officers attend military schools in the United States and France, but foreign governments do not influence officer appointments or other personnel decisions in the TAF. Western governments have, however, sought to influence strategic planning and capabilities development processes.

TAF Social Media Engagement

Facebook

Facebook

Likes

43,814

43,814

Followers

44,541

44,541

Talked About

520

520

Nation Building and Citizenship

Tunisia has employed conscription since independence as a means of strengthening the bonds of citizenship and national unity among Tunisian youth while providing for national defense. In theory, all able-bodied men are liable for a year of military service at the age of twenty, but in practice thousands avoid conscription. In 2017, a mere 506 of the 31,000 liable to serve were actually conscripted, suggesting that the TAF’s influence on nation building and citizenship through compulsory military service is overdrawn.

Military officers tend to be Francophile and anti-Islamist, and to express a preference for secularism, modernization, women’s emancipation, and liberalization of social practices. Islamists are poorly represented in the military. Likewise, recruits from southern and interior regions of the country, who tend to have more conservative views, make up a majority of enlisted personnel but are under-represented in the officer corps, which favors officers from the Sahel.

This balance has shifted since 2011. Previously, nearly 40 percent of officers appointed to the Supreme Council of the Armies and approximately 70 percent of appointments at the ranks of colonel and above came from the Sahel, which accounts for 24 percent of Tunisia’s population. The TAF command was reshuffled in 2013 to include more officers from the interior, and in 2015 the president pledged to maintain the break from favoring the Sahel.

A career as a military officer is desirable for the social prestige and reliable compensation it offers, and an enlisted career is seen as desirable in economically under-served areas of the interior and south. Senior officers are rarely, if ever, associated with corruption or profiteering from political connections. The TAF is perceived to comply with the law, rather than protect a specific political elite or social class, and to have been amenable to reform and civilian oversight following the 2011 transition.

The TAF is popular even in regions traditionally underrepresented in the officer corps, due in part to the military’s economic development projects, especially in remote parts of the country. The TAF built a network of roads linking several southern cities, and it conducts land reclamation and infrastructure maintenance throughout the country, contributing to its image as the people’s armed forces. TAF performance in counterterrorism, peacekeeping, and disaster response also positively influences public opinion. Discussion of defense affairs among civilians and the media has become more open since 2011, but the lack of civil-military cooperation doctrine or units hinders the TAF’s ability to influence nation building.

The armed forces have made a formal commitment to recruiting and integrating women, but appear to lack an official plan for making this happen, apart from some discussion of extending conscription to include women. Seven percent of TAF personnel are female, and no women have reached general officer rank, nor are they assigned to combat units, but they are found in fields as diverse as communications, engineering, military police, remote sensing, and fixed and rotary wing transport.

Military officers tend to be Francophile and anti-Islamist, and to express a preference for secularism, modernization, women’s emancipation, and liberalization of social practices. Islamists are poorly represented in the military. Likewise, recruits from southern and interior regions of the country, who tend to have more conservative views, make up a majority of enlisted personnel but are under-represented in the officer corps, which favors officers from the Sahel.

This balance has shifted since 2011. Previously, nearly 40 percent of officers appointed to the Supreme Council of the Armies and approximately 70 percent of appointments at the ranks of colonel and above came from the Sahel, which accounts for 24 percent of Tunisia’s population. The TAF command was reshuffled in 2013 to include more officers from the interior, and in 2015 the president pledged to maintain the break from favoring the Sahel.

A career as a military officer is desirable for the social prestige and reliable compensation it offers, and an enlisted career is seen as desirable in economically under-served areas of the interior and south. Senior officers are rarely, if ever, associated with corruption or profiteering from political connections. The TAF is perceived to comply with the law, rather than protect a specific political elite or social class, and to have been amenable to reform and civilian oversight following the 2011 transition.

The TAF is popular even in regions traditionally underrepresented in the officer corps, due in part to the military’s economic development projects, especially in remote parts of the country. The TAF built a network of roads linking several southern cities, and it conducts land reclamation and infrastructure maintenance throughout the country, contributing to its image as the people’s armed forces. TAF performance in counterterrorism, peacekeeping, and disaster response also positively influences public opinion. Discussion of defense affairs among civilians and the media has become more open since 2011, but the lack of civil-military cooperation doctrine or units hinders the TAF’s ability to influence nation building.

The armed forces have made a formal commitment to recruiting and integrating women, but appear to lack an official plan for making this happen, apart from some discussion of extending conscription to include women. Seven percent of TAF personnel are female, and no women have reached general officer rank, nor are they assigned to combat units, but they are found in fields as diverse as communications, engineering, military police, remote sensing, and fixed and rotary wing transport.

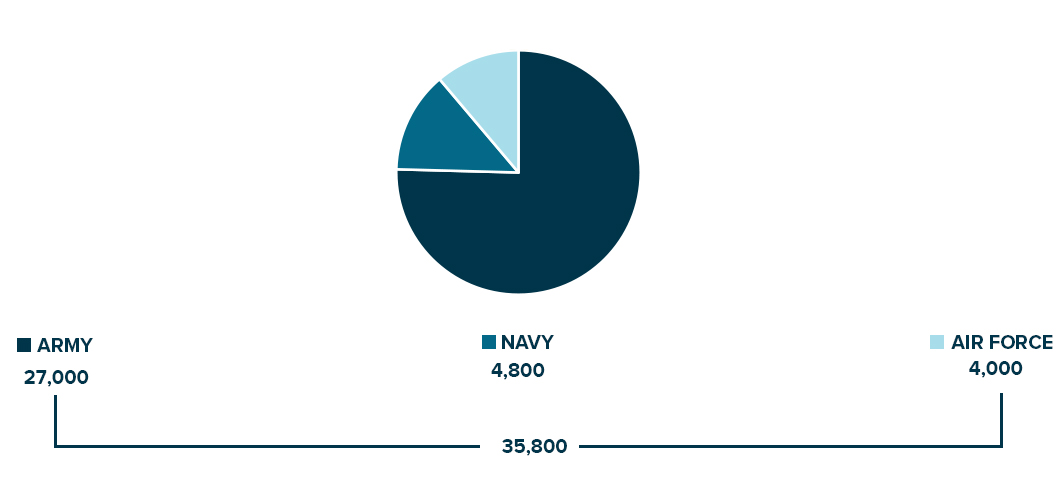

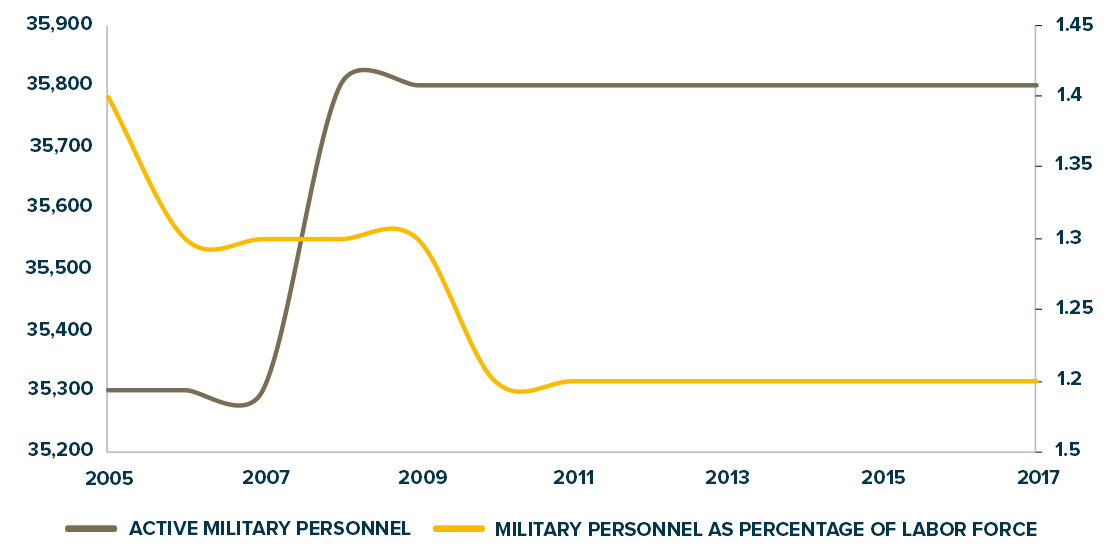

Active Military Personnel Versus Labor Force

Budget and Economy

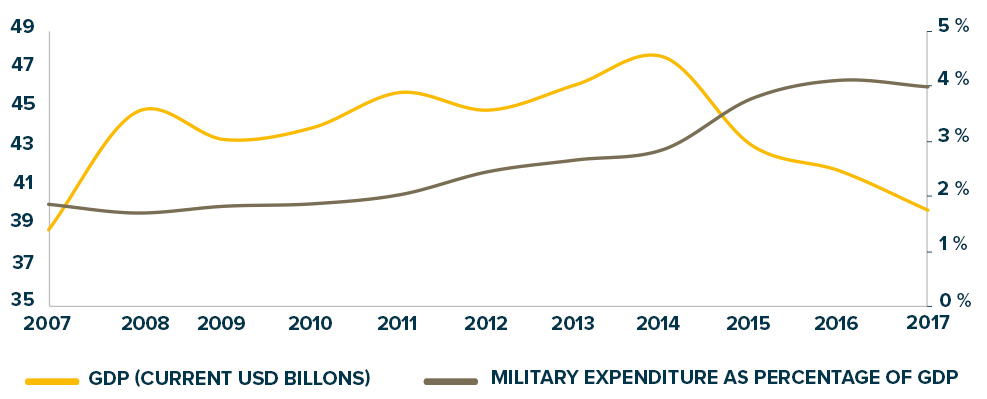

The defense budget is published as part of the annual state budget. It is accessible in detail and subject to public debate. Parliamentary scrutiny of the defense budget increased after 2011, and especially after the publication of the new constitution in 2014. These institutional mechanisms are effective at ratifying defense budgets, but of only limited effectiveness in determining actual defense needs and strategic direction. Owing to this, and to limited overall national resources, defense funding appears to be insufficient.

The TAF works with foreign partners, nongovernmental organizations, and media in a de facto policy of openness on defense finances, but local organizations generally lack the expertise to follow defense programs and so rarely question defense spending. Nonetheless, the TAF does not hide financial resources, and defense needs are the determining factor in negotiating arms deals and foreign military assistance. The government approves foreign military assistance, which constitutes a crucial complement to the defense budget. The United States tripled its military assistance to Tunisia in 2015. The United States, Japan, and European Union countries led by France and the United Kingdom have provided assistance in counterterrorism capabilities and the capacity to monitor and stop migration flows.

National defense spending has increased in parallel. The military has been drawn increasingly into counterterrorism operations alongside the police and security agencies since 2011, especially after Islamist militants infiltrating from Libya killed 54 individuals in the border town of Ben Guerdane in March 2016. The TAF played a central role in restoring control over the town, and the government increased defense allocations significantly to allow acquisition of badly needed helicopters, missiles, and machine guns. National defense spending peaked a year later, at 2.35 percent of gross domestic product, but has reduced slightly since.

The Tunisian military does not control significant portions of the economy, reducing problems with corruption. Successive governments have conducted corruption investigations and ordered the arrest of police officers, customs officials, and businessmen, but the TAF has not been shown to engage in illicit income-generation. The TAF reports all income from its limited business activities to civilian authorities, which have active and effective means at their disposal to deal with corruption risks in defense procurement.

The military does not intervene in setting national economic policy. TAF officers do not lobby the government for resources. Despite increases after the Ben Guerdane attack, the defense budget has hovered around $1 billion per year (not including foreign assistance), which is not excessive given Tunisia’s turbulent security environment, with terrorism at home and an ongoing civil war in neighboring Libya. The TAF also provides regular employment to 35,000 military personnel, which is particularly important for the lower-income classes living in the interior and the south. Overrepresentation of these areas among the rank and file means that a military paycheck may be all that prevents families from descending into poverty.

The TAF works with foreign partners, nongovernmental organizations, and media in a de facto policy of openness on defense finances, but local organizations generally lack the expertise to follow defense programs and so rarely question defense spending. Nonetheless, the TAF does not hide financial resources, and defense needs are the determining factor in negotiating arms deals and foreign military assistance. The government approves foreign military assistance, which constitutes a crucial complement to the defense budget. The United States tripled its military assistance to Tunisia in 2015. The United States, Japan, and European Union countries led by France and the United Kingdom have provided assistance in counterterrorism capabilities and the capacity to monitor and stop migration flows.

National defense spending has increased in parallel. The military has been drawn increasingly into counterterrorism operations alongside the police and security agencies since 2011, especially after Islamist militants infiltrating from Libya killed 54 individuals in the border town of Ben Guerdane in March 2016. The TAF played a central role in restoring control over the town, and the government increased defense allocations significantly to allow acquisition of badly needed helicopters, missiles, and machine guns. National defense spending peaked a year later, at 2.35 percent of gross domestic product, but has reduced slightly since.

The Tunisian military does not control significant portions of the economy, reducing problems with corruption. Successive governments have conducted corruption investigations and ordered the arrest of police officers, customs officials, and businessmen, but the TAF has not been shown to engage in illicit income-generation. The TAF reports all income from its limited business activities to civilian authorities, which have active and effective means at their disposal to deal with corruption risks in defense procurement.

The military does not intervene in setting national economic policy. TAF officers do not lobby the government for resources. Despite increases after the Ben Guerdane attack, the defense budget has hovered around $1 billion per year (not including foreign assistance), which is not excessive given Tunisia’s turbulent security environment, with terrorism at home and an ongoing civil war in neighboring Libya. The TAF also provides regular employment to 35,000 military personnel, which is particularly important for the lower-income classes living in the interior and the south. Overrepresentation of these areas among the rank and file means that a military paycheck may be all that prevents families from descending into poverty.

National Defense

Impact of U.S. Security Assistance

Since 2011, and especially since 2015, U.S. security assistance has focused on counter-terrorism, border security, logistics, air-ground coordination, and intelligence. Much of this has been accomplished through train-and-equip programs, professional military education, and combined exercises, as the U.S. Department of Defense recognizes that improving Tunisian civil-military relations and elected civilian oversight over the Tunisian military’s budgetary, acquisitions, and planning processes is essential. Various U.S. entities have provided this support, but the results have been mixed, due to U.S. limitations on what could be funded and factors like stove-piping, distrust, and excessive secrecy on the Tunisian side.

The U.S. National Defense University has tried to foster better civil-military relations by hosting yearly delegations from Tunisia’s National Defense Institute, a graduate military course meant to break down institutional barriers between senior civil servants and military officers. It helped the Institute draft a defense White Paper, but it did not result in a wider strategic review. Similarly, an Institutional Capacity Building initiative sought to shepherd a Tunisian strategic planning effort, but this collapsed due to lack of senior-buy in and civilian turnover within the Tunisian Ministry of Defense. Those involved in this effort recognized the importance of bolstering parliamentary-military transparency and trust, but achieving this is difficult and has not been treated as a priority.

In early 2020, a program was approved to embed U.S. advisors in the defense ministry, where daily, face-to-face interactions would build a culture of openness and trust, and also help the U.S. shape civil-military relations. However, this program to address strategic planning and other institutional capacity shortfalls was put on hold due to COVID-19 restrictions.

The U.S. National Defense University has tried to foster better civil-military relations by hosting yearly delegations from Tunisia’s National Defense Institute, a graduate military course meant to break down institutional barriers between senior civil servants and military officers. It helped the Institute draft a defense White Paper, but it did not result in a wider strategic review. Similarly, an Institutional Capacity Building initiative sought to shepherd a Tunisian strategic planning effort, but this collapsed due to lack of senior-buy in and civilian turnover within the Tunisian Ministry of Defense. Those involved in this effort recognized the importance of bolstering parliamentary-military transparency and trust, but achieving this is difficult and has not been treated as a priority.

In early 2020, a program was approved to embed U.S. advisors in the defense ministry, where daily, face-to-face interactions would build a culture of openness and trust, and also help the U.S. shape civil-military relations. However, this program to address strategic planning and other institutional capacity shortfalls was put on hold due to COVID-19 restrictions.

Prior to the 2011 transition, coup-proofing dynamics in Tunisia undermined the TAF’s ability to deliver efficiently on its national defense mission. Suspicious political authorities and ever-present intelligence agencies discouraged officers from meeting in social settings, and the resources of the General Department for Presidential Security and Ministry of Interior dwarfed those of the military. The 2011 transition delivered a severe blow to the military’s institutional rivals, and successive post-transition governments have increased the TAF’s capabilities to fight terrorism and perform its primary national defense role. The TAF nonetheless faces continuing gaps in resourcing, capability development, strategic planning, and national security decisionmaking.

The defense sector is open to foreign providers of military assistance supporting systemic functions, such as acquisitions, long-term defense planning, counterterrorism, and counter-radicalization. In 2015, the United States designated Tunisia a major non-NATO ally, making more resources available for capabilities development. Tunisia signed ten agreements with the United States to provide the TAF with advanced military equipment, including Black Hawk helicopters, and other assistance worth more than $142 million. In 2019–2020, Tunisia purchased over $550 million worth of aircraft and related equipment from the United States, and military cooperation is ongoing with Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Japan, the United Kingdom, and Tunisia’s traditional ally, France.

The TAF has begun expanding the roles open to women and adjusting training and personnel policies to accommodate female personnel. No women serve in senior military positions in Tunisia, but Tunisia adopted a national action plan for gender equality in 2018 and forty women currently serve as fighter pilots. The TAF has also adjusted and adapted its rules and regulations, training programs, and facilities to integrate women, primarily in training schools and in the navy and air force.

The TAF is slowly grasping the need to recruit and cultivate civilian expertise. The military relies on civilian experts to train military personnel in the collection, processing, and utilization of data, and relies on information technology departments and simulation centers to support planning and decision making processes. However, it remains more likely to use civilian experts in technical fields like financial management and information technology, than in military education, strategic planning, procurement, and intelligence. The military has no specific programs or coordinated planning to develop civilian expertise, and recruits civilian experts only as needs arise.

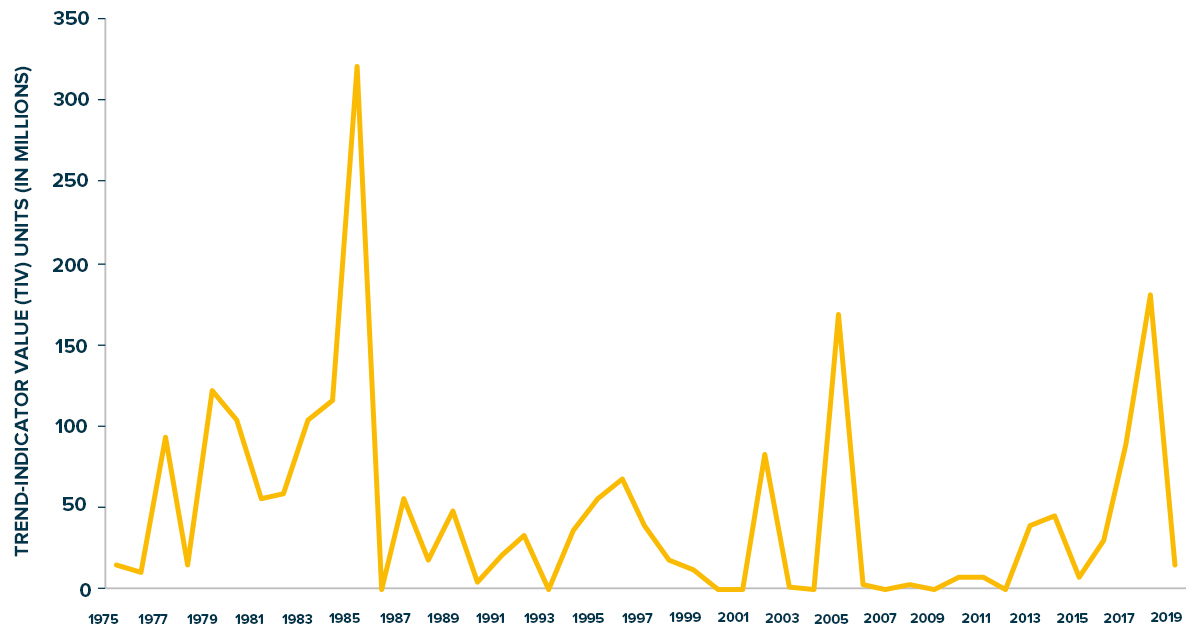

Arms Imports

Note: The TIV is a unit of measure developed by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) to calculate the volume of international transfers of major conventional weapons. It does not represent actual prices and cannot be directly compared with figures for GDP or military spending.

Source: SIPRI